|

DIVULGAÇÃO

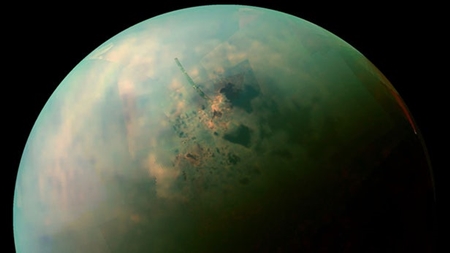

Alien-ocean-in-a-lab experiments produce new crystals not found on Earth. With Earth-like canyons and oceans of liquid methane, Saturn's moon Titan is one of the most fascinating places in the solar system. To better understand this weird world, scientists recreated Titan's alien oceans in the lab, producing new types of crystals that don't occur naturally on Earth but may form a common crust on Titan. So far, Titan is the only place besides Earth that's known to host liquid lakes and oceans on its surface. But rather than plain old water, those bodies are filled with liquid hydrocarbons of methane and ethane. It's hard to really imagine the physics behind that, so recently a NASA team brewed up the mixture under conditions that mimic the atmosphere of Titan. A near-infrared view of Titan's northern hemisphere, with the orange areas highlighting where crystals of butane and acetylene form as the weird oceans evaporate. (Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Space Science Institute)

It's not just about the ocean itself but what's left behind after the liquid evaporates. Benzene crystals were the first thing to appear. These normally take the molecular form of a hexagonal ring of carbon atoms, but in this case there was one unexpected difference – ethane molecules were trapped inside, which creates what's known as a co-crystal. But the more common co-crystal was a weird mix of acetylene and butane. These elements usually take the form of gases here on Earth, but in the chilly climes of Titan they solidify into crystals. The researchers suggest that these crystals would form a crust on the ground as the liquids evaporate away, like the salt left behind on the shorelines here on Earth. These kinds of deposits, called "bathtub rings" by the team, have been predicted based on data gathered by the Cassini mission, which detected evidence of evaporated material left behind in old, dried lakebeds. But thanks to the hazy atmosphere, we won't know for sure until some kind of spacecraft is sent to investigate. There's even a chance that the moon could be home to non-water-based lifeforms. The research will be presented at the 2019 Astrobiology Science Conference in Seattle this week. By Michel Irving. American Geophysical Union. Posted: June 25, 2019. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||