|

CULTURA DA QUÍMICA

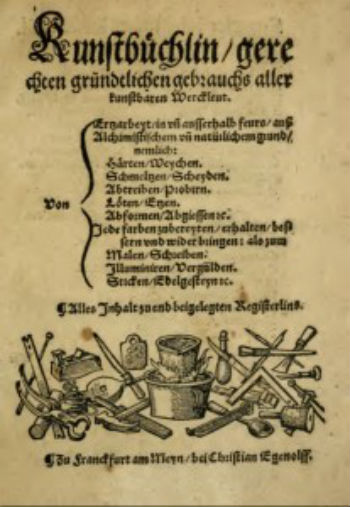

Practical Alchemy in the Renaissance. In 1535, the German printer Christian Egenolff, who had recently set up shop in Frankfurt, published a 45-page booklet titled Kunstbüchlein (Little Book of Skills). This rough little pamphlet, cheaply printed on coarse paper just in time to be offered for sale at the Frankfurt Book Fair that year, would hardly seem a likely candidate to spark a revolution. But, in many ways, it did just that: Not a scientific revolution, but a revolution in how people thought about a science that had long been regarded—for good reason—with suspicion and distrust.

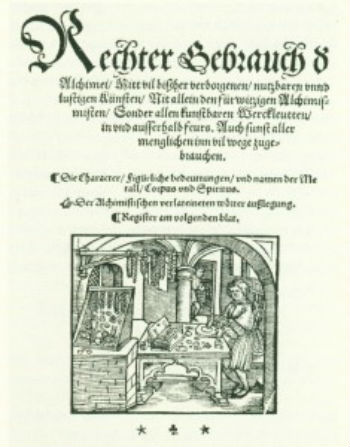

Egenolff created his booklet by combining four previously-published tracts: Rechter Gebrauch d’Alchimei (The Proper Use of Alchemy), a booklet of metallurgical techniques; Artliche Kunst (Pretty Skills), containing recipes for artists’ ink and paint; Von Stahel und Eysen (On Steel and Iron), a manual describing techniques for hardening and tempering steel and iron; and Allerley Mackel und Flecken...aus zubringen (How to Remove Spots and Stains), a booklet on dyeing and cleaning fabrics. All four of these tracts had been published in 1531-1532 as individual manuals by different German printers. It was Egenolff who got the bright idea of combining them to make a comprehensive all-purpose manual of household and industrial technology.

Egenolff made every effort to demystify alchemy, even including a glossary of alchemical symbols and terms. Driving home the distinction between the “proper use of alchemy” and abuse of the art, Egenolff concluded the work with a doggerel verse, warning, Smoke, ash, many words, and infidelity, Deep sighing and toilsome work, Undue poverty and indigence. If from all this you want to be free, Watch out for Alchemy.

Egenolff’s little “skills booklet” caught on in popular culture. The work was reprinted, excerpted, and translated into Dutch, English, and Italian, and its technical recipes turned up in countless books of secrets of the day. Aspiring craftsmen learned new trade skills from the work, while ordinary readers learned trade secrets that were formerly mysteries. Technical recipe books like Egenolff’s Kunstbüchlein translated craft secrets into simple rules and procedures, and replaced the artisan’s cunning with the technologist’s know-how.  Cornelis Bega, "The Alchemist" (1663) Getty Museum

Meanwhile, the practical alchemy of the jeweler’s workshop and the assayer’s laboratory continued to provide employment and wealth to the growing middle class. And printers such as Christian Egenolff, through their humble recipe books teaching the “proper use of alchemy,” contributed to the growing awareness that humanity’s lot could be bettered not by magic or cunning, but simply by knowing “how to.” Bibliography William Eamon, Science and the Secrets of Nature: Books of Secrets in Medieval and Early Modern Culture (Princeton, 1994). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||