|

CULTURA DAS CIÊNCIAS 9 black chemists you should know about. UPDATE: This story was updated on Feb. 21, 2020, to include profiles of St. Elmo Brady, Mary Elliott Hill, and Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. At the time, Callender says the achievements of black scientists were rarely celebrated. He learned about only one chemist who looked like him: George Washington Carver. “Nothing was ever talked about that ever had to do with people of color,” he says. “Whatever role models you got, you got in your community.” As a doctor, Callender led one of the largest pushes in the nation to improve organ-donation rates within minority groups. Looking back on his life, Callender credits the role models he had, as well as his own determination and religious beliefs, as critical in making him the leader he is today. He thinks that it is important for young students to see and learn about black ingenuity in the generations before them. “It’s critical to learn about them,” he says, because it reinforces aspiration. “Their unreachable stars become reachable.” In celebration of Black History Month, C&EN is profiling nine black chemists who made contributions to a wide range of disciplines. This list is not comprehensive and is focused on scientists who are no longer alive. We want to continue to add to this list and we want to hear from you: Who are black chemists, living or dead, whose work or life story inspires you? Comment below to send us your suggestions. Alice Ball  Credit: Wikimedia Commons Alice Ball

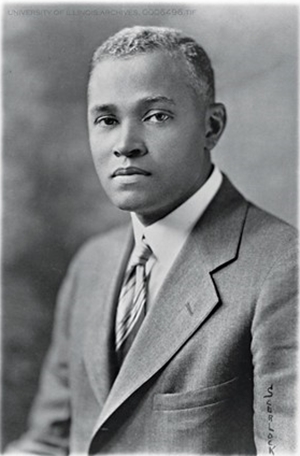

In 1916, Harry Hollmann, a doctor at Kalihi Hospital who was treating people with leprosy, asked Ball to help him determine the active ingredients in chaulmoogra, a plant that had been used with some success to treat the disease. Hollmann was looking to isolate something concentrated and injectable, and in one year, Ball had figured out how to fractionate the active oil, allowing her to solubilize it (Arch. Derm. Syphilol. 1922, DOI: 10.1001/archderm.1922.02350260097010). Ball died suddenly, at the age of 24, possibly of accidental chlorine poisoning in a laboratory. Her work was taken up by a male scientist who tried to take credit for her discoveries. Chaulmoogra injections based on Ball’s work became a standard treatment for leprosy until the 1940s. In 2000, Hawaii Lieutenant Governor Mazie Hirono named Feb. 29 “Alice Ball Day.” St. Elmo Brady  Credit: University of Illinois Archives St. Elmo Brady

Several years later, Brady returned to Fisk University, where he had earned his undergraduate degree, to lead its chemistry department. He took over from another noted black chemist, Thomas W. Talley. At Fisk, Brady created the nation’s first graduate program in chemistry at a historically black college and eventually did the same at three other universities. In 2019, the American Chemical Society designated the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Fisk University, Tuskegee University, Howard University, and Tougaloo College National Historic Chemical Landmarks because of the work that Brady accomplished at those institutions. He died in 1966. Lloyd Noel Ferguson  Credit: Cal State LA Lloyd Ferguson

Eventually Ferguson switched coasts, moving to Howard University to teach and lead that school’s chemistry program. As a researcher, he studied several topics, including the chemistry of taste. He was part of the team that created Howard’s chemistry doctoral program, the first at any historic black college or university. Ferguson was relentless in creating opportunities for black people interested in chemistry and biochemistry and received a Guggenheim Fellowship. He was one of the cofounders of NOBCChE, the National Organization for the Professional Advancement of Black Chemists & Chemical Engineers. The organization named an award after him that reflected his passion for bringing up the ranks of young black chemists—the Lloyd N. Ferguson Young Scientist Award for Excellence in Research. He died in 2011. Bettye Washington Greene  Credit: Science History Institute/Wikimedia Commons Bettye Washington Greene

While at Dow, she worked on developing colloids and on ways to improve latex. She published several papers related to work in developing polymers, including studying different properties that lend to the redispersement of latex. Among Greene’s many accomplishments are several patents related to latex, including a latex-based adhesive using a carboxylic acid copolymerizing agent, and latex polymers with phosphates used as coatings. Greene died in 1995. Walter Lincoln Hawkins  Credit: National Science & Technology Medal Foundation Walter Lincoln Hawkins

Enter Walter Lincoln Hawkins, a chemist at Bell Laboratories and the company’s first black employee in a technical position. He and a partner developed a cable sheath made of a then-new class of thioether compounds and carbon black, combined with polyethylene. The work improved the lifespan of telecommunication cables to up to 70 years and led to the expansion of telecommunications all over the world. This sheath was one of dozens of products patented by Hawkins in his lifetime. He eventually became the director of Bell’s research laboratory and was inducted into the National Inventor’s Hall of Fame. Hawkins believed strongly in mentoring minority students, leading a project by the American Chemical Society to promote chemistry as a subject and a profession. In 1992, President George H. W. Bush awarded him the National Medal of Technology & Innovation, in part for his work in helping rural communities establish telephone communications. He died just two months later. Alma Levant Hayden  Credit: NIH History Office/Wikimedia Commons Alma Levant Hayden

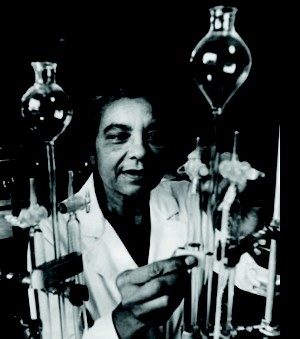

Except that it wasn’t, and Alma Levant Hayden, then a scientist at the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, showed the world why. After federal researchers coaxed the tiniest samples from the doctor and his partner, Hayden analyzed krebiozen. The results were stunning. This compound being touted as a cancer cure was nothing more than creatine, a molecule readily available in our diets. Hayden was among the first federal scientists of color, working at what would become the National Institutes of Health and then the Food and Drug Administration. She specialized in using spectrometry to detect steroids. At a career forum for young women in 1962, Hayden told the mostly high school attendees, “Always try to do the very best and to be the very best in whatever group you are working with.” She died in 1967. Mary Elliott Hill  Credit: Louisville Courier Journal Mary Elliott Hill

Hill was born in 1907 in South Mills, South Carolina. She earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1929 from what would eventually be called Virginia State University. Throughout her career, she taught high school– and college-level chemistry. In 1951, she became the head of the chemistry department at Tennessee State University, eventually leaving to become a professor at Kentucky State College when her husband was named the school’s president. Robert Henry Lawrence Jr.  Credit: Newscom Robert Henry Lawrence Jr.

Soon after, the Air Force selected him to become an astronaut to work on low-orbit intelligence missions. This program was the precursor to the NASA’s space shuttle program. During his training, Lawrence also got a PhD in physical chemistry from the Ohio State University. Lawrence never made it into space. In 1967, he died during a training flight at Edwards Air Force Base. He had completed about 2,500 hours of flight time in his short career. Bradley University named a scholarship in Lawrence’s honor, and a school in Chicago was also named for him. On Feb. 14, 2020, a shuttle bearing Lawrence’s name embarked for the International Space Station, carrying, among other things, supplies for scientific research. Samuel P. Massie  Credit: US Naval Academy Samuel P. Massie

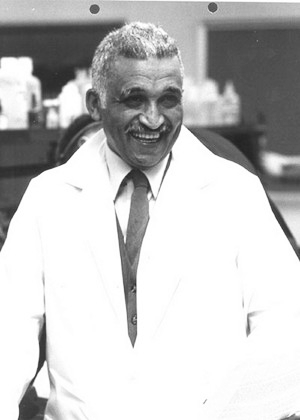

Massie eventually got his Ph.D. from Iowa State University and then worked on finding new antimicrobial compounds. In 1982, he patented an antibiotic for treating gonorrhea. In his career, he also focused on education—teaching chemistry and taking an appointment at the National Science Foundation to shape science education across the nation. In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson chose him to teach chemistry at the US Naval Academy, making him the first black person to do so. Many years later, he chaired the department, becoming the first black person to hold that position. Massie was always a high achiever, graduating high school at 13 and college at 18. One of his Manhattan Project contemporaries was another accomplished black scientist named Lloyd Albert Quarterman. Massie died in 2005. Chemical & Engineering News. Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society. Accessed: June 05, 2020.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||