|

DIVULGAÇÃO

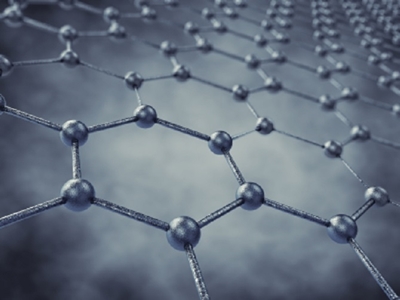

Graphene for physicists, materials scientists, and engineers. In the weeks since the Physics World team kicked off the new year by testing a pair of graphene headphones, we’ve received a steady stream of comments about our review and a related segment on our weekly podcast. A few people have asked our opinion of other graphene headphones, and one man went so far as to question whether the “graphene” label he found on an inexpensive pair of headphones was anything more than “misleading click-bait”. I can’t judge any product I haven’t tried, and I also can’t judge a product’s graphene content without taking it apart and getting experts to analyse it. However, with those two caveats firmly in place, here are two facts to consider should you happen to be in the market for graphene headphones (and, by extension, graphene anything).  Graphene sheet model. (Courtesy: iStock)

Second, graphene exists in many forms, with many price points. A lot of physicists are interested in ultra-pure, single-layer graphene, which has amazing electronic properties. This “physicists’ graphene” is difficult (and expensive) to make in macroscopic quantities. However, others are more interested in graphene’s mechanical properties, such as strength and rigidity. To get these properties, you don’t need ultra-pure single-layer graphene. You can get by with a cheaper type, which for argument’s sake I will term “materials scientists’ graphene” (this is an oversimplification, but it conveys the right feel). The proprietary graphene-based material in the headphones I tested was most likely in this category. But even this type of graphene is expensive relative to a third type of graphene, which is cheap enough to be added in bulk to substances like paint or resin to improve their heat transport and/or electrical conductivity. As I understand it, this “engineers’ graphene” functions like a superior version of graphite, and manufacturers are selling it by the kilo (and maybe, soon, by the tonne). I’m not trying to start a three-way brawl between physicists, materials scientists and engineers about which type of graphene is better. They all have their uses, and they all qualify as graphene. But here’s the problem: a product can advertise itself, accurately, as containing graphene even if the graphene it contains is not of a type or quantity that’s going to make a difference to its performance. What’s more, if an unscrupulous manufacturer wants to put graphite in its product and call it “graphene”, it’s hard for ordinary consumers to know the difference. To the naked eye, graphene and graphite both look like gritty black powders. You need more sophisticated testing equipment to distinguish between them, and between the various grades of graphene. Certification is a huge issue for the graphene industry, and a lot of people are working on it. However, until there’s a strong framework for regulation, the next best thing is probably to look for independent endorsements by people and organizations who know what they’re talking about. The headphones I tried were endorsed by the co-discoverer of graphene, Kostya Novoselov, as making good use of the material. Since then, I’ve learned of a different make of graphene headphones that has been endorsed by an industry body called the Graphene Council. However, until someone gives Physics World its own product-testing lab and qualified technicians to run it, that’s about all I can say – except to add that there are some graphene products I definitely won’t be testing with my colleagues. By Margaret Harris. Physics World. Accessed: Feb. 07, 2020.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||