|

NOVIDADES

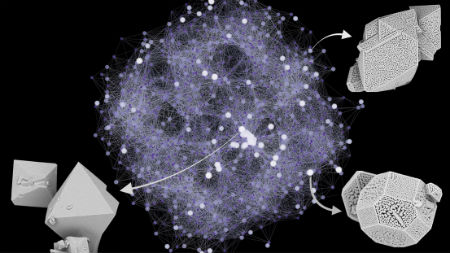

A new discovery is rarely the result of one successful experiment. Rather, it is usually born from a long process of trial and error – combined with a healthy dose of intuition that the scientists have honed over the years. But sharing knowledge about failed attempts could make research easier for everyone, especially in the field of chemical synthesis. That’s what a team of chemists from EPFL’s Laboratory of Molecular Simulation (LSMO) have recently shown in an article appearing in Nature Communications.  © LSMO/ EPFL

The hitch is that developing new MOFs requires a huge amount of time and energy. This kind of chemical synthesis involves optimizing many different variables – solvent composition, temperature, and reaction time, to name just a few. And the more variables there are, the higher the number of possible combinations; researchers can easily find themselves with millions of experiments to carry out to come up with just one MOF. What’s more, the chemical links and assembly processes underlying the formation of MOFs are still not fully understood, meaning there are not yet any basic principles that chemists can follow. They essentially have to start from scratch each time. His team took as an example an MOF that is well known to scientists: HKUST-1. Its crystalline structure can vary depending on what chemical group is used to synthesize it. To measure how extensively intuition plays a role in synthesizing the right kind of material, the LSMO chemists first used a method that does not rely on intuition at all – a high-performance robotic synthesizer. Their synthesizer processed no less than nine different variables to reverse engineer the process and compile all possible failed synthesis experiments for an HKUST-1 molecule. “Our robot can crunch through about 30 chemical reactions a day. But even with that high level of throughput, it would still take nearly ten billion days to run through all possible reaction combinations. So researchers working under normal conditions – that is, without a robot – clearly have to rely on intuition to rule out a vast number of possible combinations and focus on the most promising,” says Kyriakos Stylianou, head of chemical synthesis at LSMO. In other words, whether they realize it or not, researchers who carry out several experiments – successful and otherwise – get a feel for what will work and what won’t. This “gut feeling” tells them which variables could have the greatest influence on the outcome of a chemical reaction. For example, if a scientist finds that changing the reaction temperature alters the results of his experiment, even slightly, then he will be more likely to focus on the temperature variable. “Now we need to convince scientists to open up and talk about their unsuccessful experiments. If we’re able to do that, we can dramatically change the way chemical research is performed,” says Smit. By Sarah Perrin. Mediacon. EPFL. Posted: Feb 01, 2019. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||