|

NOVIDADES

Among other things, hydrophobic (water-repelling) surfaces can be used to keep medical devices germ-free, to help airplane wings shed ice, and to keep solar panels clean. A new process could soon make those surfaces much more durable, allowing them to ward off water for a longer time. Most of the hydrophobic surfaces we've seen incorporate "forests" of nanostructures that protrude upwards from the substrate. Because water droplets are unable to get down in between these structures, they instead bead up on top and then roll off. As they do so, they carry dirt, germs or other contaminants with them. Unfortunately, though, those nanostructures are often quite fragile. This means that through regular wear and tear, they're often cut or abraded away. As a result, the surface loses its hydrophobicity in those areas.  Hydrophobic surfaces cause water to bead up and roll off – and superhydrophobic surfaces do so even more. yurok.a/Depositphotos

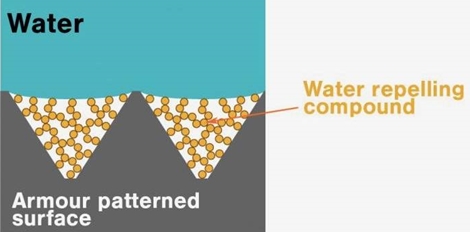

Their process involves first etching a honeycomb-pattern grid of nanoscale inverted pyramids onto a substrate such as metal, glass or ceramic. A superhydrophobic chemical coating is then applied to the inside of the pyramids. When an instrument such as a sharp blade or a piece of sandpaper is subsequently drawn across the armored surface, the ridges between the pyramids keep it from getting down inside, protecting the coating within.  A cross-sectional diagram of the armor. Aalto University

"We made the armor with honeycombs of different sizes, shapes and materials," says Aalto's Prof. Robin Ras. "The beauty of this result is that it is a generic concept that fits for many different materials, giving us the flexibility to design a wide range of durable waterproof surfaces." A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Nature. Aalto University. Posted: June 04, 2020.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||